Operation Paperclip:

Secret German Postwar Project

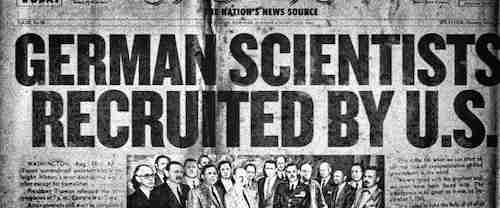

More than 1,500 German scientists, engineers and technicians (many of whom were formerly registered members of the Nazi Party, some were party leaders) were recruited and brought to the United States. After World War II they were hired under Operation Paperclip by the U.S. government to gain scientific and military advantage during the Cold War and, later, Space Race. (Paperclips were attached to the scientists’ new work as U.S. Government Scientists, thus the name.)

To compare to the U.S. project, over 2,000 scientists were aggressively recruited by the Soviet Union (and recruited by gun point) during one night.

Other post-war Allied countries snapped up some German scientists as well, and there were many who came to various sites in the U.S. About 86 aeronautical engineers were transferred to Wright Field (now Wright-Patterson Air Force Base) where captured Luftwaffe aircraft and equipment were located. A few scientists were investigated many decades after they were included in Paperclip, and because of their Nazi activities, were deported to West Germany.

Why bring this up?

Wright Field was one of the sites to which the Paperclip Germans came, and some lived in this area until death. And the Enon Community Historical Society (ECHS) is fortunate to have had an Enon resident speak of his experience working on Paperclip—Clem Schmid worked on the American side of the German Paperclip on the base (Clem was not a German or Nazi).

Clem and his wife Mary Ann are volunteers with ECHS. Clem shared his Paperclip experience in a “Rocking Chair” program the society hosts occasionally with those who have interesting memories. He said he learned German, but the Germans already knew English, so coordination was easier.

One famous Paperclip Nazi was Werner Von Braun who was a nuclear physicist developing the V-2 rocket. Von Braun worked on the U.S. rocket program, although it was discovered he had a questionable background as a Nazi who knew of torturing and murder of prisoners in the V-2 German project.

In recent years a thorough history, Operation Paperclip, was written by Annie Jacobsen (who also wrote a study, Area 51). Throughout Jacobsen’s book Wright Field was mentioned about various points about Paperclip scientists and their work.

What is clear is that American industry could benefit from a different kind of restitution: knowledge. A few examples: Sterilize fruit juice without heat; run-proof hosiery; butter churned at 1,500 pounds per hour; yeast produced in unlimited quantities; wool pulled from sheepskins without injuring the animals’ hides; reduction of electrical components to the size of a pinkie finger; they pioneered electromagnetic tape…let alone rocketry to the moon; medical practice, insecticides, ordnance. Germans had patents on all sorts of improvements the U.S. could use.

The first group of Germans brought to Wright Field in 1945 lived in an isolated, secure housing area called Hilltop. These scientists specialized in motor research, aerodynamics, rocket fuels, supersonics, and business. Wright Field had already hosted prisoners of war who acted as cooks for the Paperclip scientists.

The yearlong Nuremburg Trials started at the end of 1945. About that time the Army Air Forces hosted a grand five-day fair at Wright Field. On display were captured German and Japanese aircraft and rockets never seen by the public until then. The displays included the V-2 rocket and Me 262. Half a million people from 26 countries came to view the marvels.

John C. Green, Commerce Department representative to this program, attended this event. With some back and forth, he appealed to President Truman to not waste these Germans who could contribute to American commerce. He mentioned as an example of success in Germany that could help the U.S. economy—Dr. O. Graff, designer of the autobahn. But as the Nuremburg Trials opened up information about the vicious work of the Nazis, it slowed the commerce connection.

In the meantime, and of interest to Dayton’s Wright-Dunbar Interpretive Center’s Parachute Museum, Dr. Harry Armstrong became the first flight surgeon and had never flown in a plane. And he then jumped from a plane to help army jumpers deal with panic and understand the physiology. Dr. Armstrong set a U.S. Army record. He joined the army for good and became one of the most important figures in American aviation and aerospace medicine. By 1934 Dr. Armstrong and his family arrived at Wright Field, where he began work on medical effects on pilots in the increasingly faster airplanes, and worked closely with several former German scientists.

The Paperclip work was very expansive and very secret. Some of the work made a difference in American life. And much of it happened right here at Wright Field (WPAFB) for several decades.

For more information about life in the Enon area, visit the Mike Barry Research Center on Indian Drive, between the old log house and the Adena Mound. The center opens regular hours March 2, or call (937) 864-7080 and leave a message, or check the society web site,http://www.enonhistory.com/index.html

Article "Operation Paperclip"© reproduced courtesy of Enon Eagle,enoneagle.net

Source: aviation trailOperation Paperclip