Dispatch from KCVN, Clovis, New Mexico: It’s chilly. It’s nearly noon and I’m wearing my winter flight jacket. As we walk across the tarmac to Race 53, above our heads the sky is solid overcast. It’s pale gray. Low, kissing the edge of marginal VFR, but slowly rising.

Not even 100 miles from home yet, we’ve been on the ground for two-and-a-half hours waiting for a line of thunderstorms to slide north and east off our flight path. We’re playing hopscotch with the weather today, jumping forward one step at a time and waiting on the ground for the sky ahead to clear enough for the next jump.

Well, that’s the plan, anyway. We’ve done one hop and no scotch at this point.

A wicked band of thunderstorms blocked Race 53’s way to the Ghost Run Air Race. But it wouldn’t be the weather that would ultimately ground the Air Racer. (Photo by William E. Dubois)

I free the rusty tie-down chains and do a quick walk-around while Rio mounts up. We have two days to get to Jasper, Texas, practically in Louisiana, for the Ghost Run Air Race, which is shaping up to be the largest Sport Air Racing League (SARL) race of the season with nearly 30 planes on the roster.

I’ll be racing a pair of Cessna 150s.

In one fluid motion I mount the wing, step over the fuselage wall, step onto the seat, and slide down into the comfortably cramped cockpit. I slide my door up over my head and fasten it into place.

Rio makes all the cockpit electronics ready while I fasten my seatbelt and shoulder harness. He plugs the GPS into the 12-volt system, connects the iPad and iPhone to the backup “juice box” in the copilot map pocket, and wakes up the wireless headsets. I swipe the iPad’s screen to link the Bluetooth between the tiny computer and the GPS receiver. Next, I activate the Cloudahoy flight tracker app, then plug our flight settings into Garmin Pilot.

Really, it takes longer to get all the modern cockpit electronics working than it does to preflight the plane.

“We ready to rock and roll?” I ask my teenage copilot.

“Let’s do this thing,” he replies.

Working from right to left, I start the engine: Throttle cracked; mixture full forward; carb heat off; mags to both; two shots of prime; master on; punch the starter. The prop spins to life and the engine catches at once. She lets out a throaty roar, then coughs, and… stops.

The prop completes one last lazy arc and freezes.

What the hell?

I work the throttle a bit and press the starter again. The prop spins round and round and round but the engine doesn’t catch. I work backwards, shutting off the master and the mags, and fully closing the throttle. What did I miss?

Rio nudges me, “Did you remember to open the fuel cutoff?”

We’ve been suffering a drippy carburetor, which is vexing because I paid a fortune to have it fully overhauled this spring, and it never dripped before the overhaul.

My mechanic spent some time on it and declared the carb would need to come off the plane and be sent back to the overhaulers again, a process that would leave us down for weeks. He judged it to be only an engine-off condition and advised me to just use the fuel cutoff when parking for any period of time for the rest of the race season, and we’d take care of it at Annual before the start of the next race season.

When we landed at Clovis I left the cutoff open, as I hoped we wouldn’t be on the ground for too long. Rio and I borrowed the crew car and ran into town for a quick breakfast.

The only good thing about a longer-than-planned layover is the opportunity to explore the local community. Air Race William E. Dubois and his son Rio took the advice of the FBO to try out Don Maria’s, an oddly-named local eatery. In Spanish, the honorific “Don” is typically reserved for males. Regardless, the food was great, and the break gave the storm time to start to move off the flight path. (Photo by William E. Dubois)

When we returned, there was a little pool of fuel on the ground behind our nose fairing, so I climbed up and closed the cutoff between the header tank and the drippy carburetor.

I reach down under the instrument panel and grasp the lever. It’s in the proper open position.

Working from right to left I try again: Throttle cracked; mixture full forward; carb heat off; mags to both; two shots of prime; master on; punch the starter. The prop spins to life and the engine catches at once. She lets out a throaty roar, then coughs, and… stops.

The prop completes one last lazy arc and freezes.

Rio removes his headset, “I’ll check with the FBO and see if they have a mechanic.”

A chance

The mechanic, we’re told, had just left for lunch five minutes ago. He’ll be back in an hour. Maybe an hour and a half. They’ve called him on his cell so he knows we’ll be waiting. We’re invited to hang out in the flight lounge.

A comfy prison: The Clovis Terminal has all the creature comforts one could ask for, but that didn’t make waiting for the out-to-lunch mechanic any easier. (Photo by William E. Dubois)

As places to wait go, I’ve been in worse. Actually, the Clovis Terminal is lovely. We were warm and dry. There were comfy chairs, good wireless Internet, clean bathrooms, vending machines, a water cooler and a Keurig Coffee machine. According to plaques on the wall, the terminal was built in 1958 and renovated in 1999.

But I was not a happy camper. Time was a-wasting. I checked the weather. I got up and paced back and forth. I checked the weather again. I got up and paced back and forth again. I listlessly surfed eBay to try to distract myself. I placed a bid on a reproduction antique board game called Air Race from Perisphere and Trylon. All the time, in the back of my mind, I was trying to make sense of why our plane wouldn’t start.

I decided it must be a fuel supply problem. Perhaps the fuel cutoff had gotten stuck. Or the fuel line had somehow gotten clogged. I actually don’t know that much about how airplane engines work, but I learn more with each breakdown, and there have been a lot of those since we became an airplane-owning family

I got up and paced back and forth.

“Relax, Dad,” Rio told me.

Right on the hour-and-a-half mark a young man with grease-stained hands enters the terminal, “Are you the FBO mechanic?” I ask him.

“Yep,” he replies, “you the guy with the broken Ercoupe?”

“William,” I say, extending my hand.

He shakes my hand, “I’m Chance.”

And I can’t help but wonder: Is he my best chance or my last chance? One thing’s for certain. He’s my only chance of making the Ghost Run.

An uncertain diagnosis

Chance gives a shot at starting Race 53. At first she roars and stops like she did for me. But by dancing with the mixture, the primer, and the throttle he somehow coaxes her to life. But she doesn’t sound right to my ear. She’s not running healthy.

Chance finally waves me over and shouts over the engine. He’s got her running but every time he advances the throttle she wants to die. He thinks it’s a carburetor issue and wants to take a closer look at his shop at the far end of Taxiway Bravo. He’s never taxied an Ercoupe before and isn’t convinced that if he shuts down any of us will be able to get her running again.

Not looking ready to race, Race 53 sits with her lower cowl and carburetor removed. The storm has passed, but the plane won’t be flying anytime soon. Note the pool of fuel on the hangar floor. (Photo by William E. Dubois)

Prop spinning, he dismounts and Rio and I climb aboard. I try to power up to get the plane rolling, but she gets rough and threatens to stall. It feels like we are stuck in mud, unable to move. Finally I’m able to edge the throttle forward enough to overcome the ground friction and the wheels start to move.

We’re off. Not to the races, but to the last chance shop.

Ring around the moon

Chance, in his pickup truck, easily beat us back to his shop. He waved us in toward the open hangar doors, then slowly raised his arms above his head into an “X,” the universal ramp language for “Stop.”

I cut the engine, unaware that we wouldn’t leave that spot.

Last night, as I loaded the car for the airport, there was a ring around the moon. As I got ready for bed, I couldn’t shake the old sailor’s storm warning from Longfellow’s Wreck of the Hesperus: “Last night, the moon had a golden ring, and to-night no moon we see!”

We all know what happened to the Hesperus. And to the skipper’s little daughter.

I, too, was traveling with my child, so the weather preyed upon my mind more than usual. Crazy, I know. We should all flight-plan as if our children were aboard every time, even when flying solo.

And while it wasn’t the Hesperus’ Hurricane threatening across my flight path — that was last week’s misery — the weather was not optimum for long distance travel. At 4:30 in the morning I was online studying my flight briefing and comparing commercial weather forecasts. Lowish ceiling across the entire route, but that wasn’t the problem.

The problem was the line of thunderstorms developing along a cold front before dawn. If they are building before the sun rises, you know they’re powerful and are going to do nothing but get larger.

So I knew even before driving to the airport that there was at least a 50% chance we wouldn’t make it. But it never occurred to me that the ring around the moon would be a portent of a mechanical failure.

After we shut the engine down, fuel spewed from the carb, filling the air filter, spilling in a great gush onto the ground. While we hung out in his office, Chance inspected the fuel-soaked engine and made a few phone calls.

He came in and announced that he regretted that in his opinion the old carb needed to be rebuilt. At least that’s what he thought until I told him it had been fully refurbished not six months before by the nation’s leading expert on antique Stromberg carbs. Then he and his father (it’s a father-son shop) put their heads together and decided that perhaps the fuel float was stuck, causing the bowl to overflow.

They could pull the carburetor off, open it up and see.

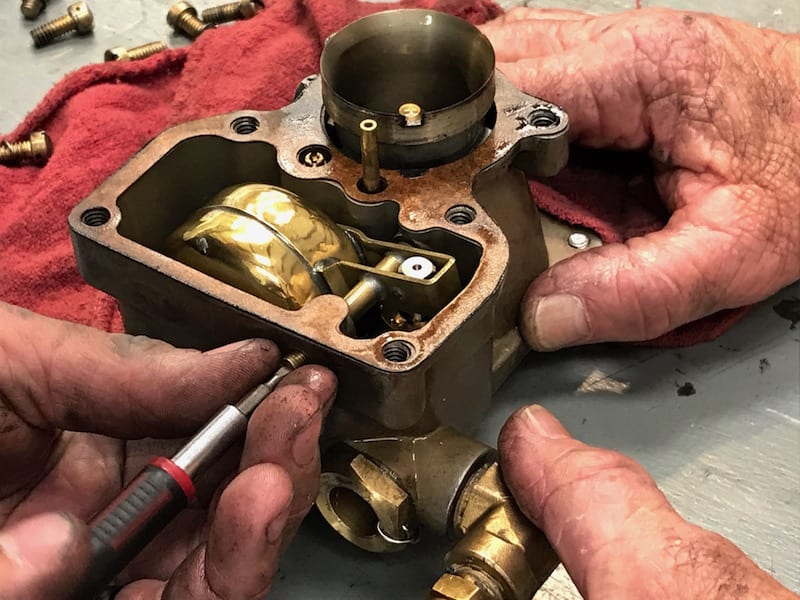

Hidden treasure: The fuel float inside the antique Stromberg carburetor is polished brass, a thing of beauty. (Photo by William E. Dubois)

I couldn’t make sense out of how too much fuel in the carb bowl would cause a running engine to suddenly stall, but I honestly didn’t know enough about engines to have an opinion, and at any rate it was true that we had a leaky carb that needed to be fixed.

So I took a chance on Chance. Not that I had a choice. My plane wouldn’t run.

A changing diagnosis

As we hung out in Chance’s office, I worried that they’d fix the carb and that the plane still wouldn’t run. To kill the time I checked the weather. Then I got up and paced back and forth. Then checked the weather again. I got up and paced back and forth again. I listlessly surfed eBay to try to distract myself.

Chance and his Dad had a helluva of a time getting the carb off the bottom of the engine, finally resorting to manufacturing strangely-shaped tools with small wrenches spot-welded on twisted lengths of tubing to reach the bolts.

Once free, they jointly carried the carburetor, as if it were a container of nitroglycerin, to a nearby workbench. Chance cut the safety wires on the bolts, unthreaded each bolt, and gingerly worked the cover of the carb free and lifted it away. I’d never seen my carb float before. It was beautiful. Shining, bright, glossy brass, glowing like pirate gold in a treasure chest.

It was also not stuck.

A smooth run

I was having a hard time reconciling our plane’s current state of ill health with how she was performing just a few hours earlier. We had a smooth, powerful run from our home base to Clovis. The plane performed flawlessly. Actually better than I’d seen for some time. Not a hiccup, not a cough. We had a smooth landing, largely executed by Rio. We taxied in with no issue and then the plane simply sat on a perfectly dry, windless ramp for a few hours and then — suddenly — wouldn’t work anymore.

Copilot Rio A. F. Dubois with a sick friend in the background. The 14-year-old student pilot wasn’t optimistic that his father would make the race. He was proven right. (Photo by William E. Dubois)

Still, the carb was now beyond dripping. It was fully leaking. The mechanics made some calls and came to the conclusion that the float was set wrong, not shutting off the fuel soon enough, causing the bowl to overflow.

While I accepted that could be true, I couldn’t see how it would dramatically change engine performance, nor how that could explain the sudden change in rate of fuel loss. Nonetheless, they had my blessing to go about resetting it.

In Chance’s office, I checked the weather. Then I got up and paced back and forth. Then checked the weather again. Then got up and paced back and forth again. I listlessly surfed eBay to try to distract myself.

A race to repair

The sun, now out, was low in the sky. I knew now that there was no issue with the fuel cutoff or supply line, as the pale blue fuel flowed freely from the header tank as Chance and his father played with the carburetor float, testing different settings and measuring the fuel levels in the bowl. They had spent the full afternoon racing to get Race 53 back in the race. Their efforts were borderline heroic, and I was grateful, but I was pessimistic about the outcome of their labors.

The carb adjusted and re-installed, the cowl buttoned up, we pushed Race 53 out of the hangar. Chance climbed into the cockpit, fiddled with the buttons and levers, and called out, “Clear!”

The prop spun. The engine caught. And ran.

Poorly. She skipped beats. The volume of the exhaust pitched up and down. Then a great cloud of white smoke came out of the exhaust, and, caught by the prop blast, flowed along the bottom of the fuselage and out onto the ramp beyond her twin tails.

It was stunning. I would have loved it, had it come from the smoke system I’ve been lusting for, rather than from a sick engine.

The motor still running, Chance’s father first opened one side of the cowl, kneeling in the narrow space between the spinning prop and the wing, and then the other, looking inside, checking, adjusting.

He stood and gave the “X” sign to his son. Chance shut down the engine and fuel spurted from the air intake and gushed out the rear of the cowl, creating a visible puddle on the ground.

It was now well past closing time.

Despite the daylong efforts of two local mechanics, Race 53 was not able to get back in the race. As the sun sets, she’s tied down awaiting more work, and the pilots had to abandon her and return home—by car. (Photo by William E. Dubois)

Standing beside Race 53, Chance seemed more bummed that I was. “I thought we had it,” he told me, shoulders slumped, “I really did.”

There would be no Ghost Run for Race 53, and no Southern Nationals. After surmounting impossible odds and making virtually every race in the season — despite other breakdowns, crazy weather, and epic distances — we would miss two of the final four, and there was no mathematical hope we’d pull ahead of our rivals. The season belonged to them.

Chance said he’d done all he could do. The carb needed to go off to an expert. He’d take it off in the morning and next-day air it to my choice of the guy who rebuilt it in the spring, or an outfit in Dallas that had never done Chance wrong. I chose Dallas.

Chance was optimistic that he’d have her up and running in time for the Grove Air Race in Oklahoma the first week of November.

“What do I owe you for the day’s efforts?” I asked.

“We’ll settle up when I get her running,” he replied.

Then I asked him where the best place in town was for a good steak and a stiff drink.

Scratch

Standing in the terminal at Clovis, the sun kissing the horizon, I emailed the League Chairman to “scratch” me from the Ghost Run. It was a painful email to send. This season I’ve had races moved and races scrubbed. But I had never had to scratch. Next, I called the hotel to cancel my reservations.

Then there was nothing left to do but go home.

By car.

My League Points: Still stuck at 1,130.

My League Standing: I missed the Ghost run, but my rivals and friends did not. I’m still in second place in the Production category, but now the Elys are a whopping 160 points ahead of me. Looking at who raced and didn’t, and the speeds clocked, I am confident that had I been there I would have closed the gap between me and the Elys to a mere 30 points. Arrrrrrrrgggg!

I also still cling to my second place overall status in the league, but Ken Krebaum picked up 100 points at Ghost, and is now right on my heels with 1,070 points. In two weeks time, I’ll fall to third place in the league following the rescheduled Southern Nationals, which I cannot attend.

Source: http://generalaviationnews.comAir Racing from the Cockpit: An ill-timed breakdown