On April 17, 2015, a Cessna 421B pilot was forced to land on a highway, when first the left engine, then the right, lost all power during climb-out from Angelina County Airport (KLFK) in Lufkin, Texas.

According to the NTSB report, the plane was “substantially damaged,” while one person sustained serious injuries and two others sustained minor injuries.

When the pilot got out of the plane on the highway, he could smell Jet A fuel.

The problem? When he asked the FBO to top off the tip tanks, he meant with 100LL.After the accident, it was discovered the FBO employee who fueled the plane mistakenly put 53 gallons of Jet A in the 421. A post-accident examination revealed signs of detonation in the engines, consistent with having been operated with Jet A.

This was part of a spate of accidents in late 2014 and 2015 directly related to misfueling.

This led the safety committee of the National Air Transportation Association (NATA) to look at misfueling. While NATA offers safety training to FBO personnel that specifically addresses misfueling, officials felt there was more that could be done.

That led to a new online training program that’s offered free to pilots, line service professionals, FBO customer service representatives and FBO managers.

The training is free to all who are interested — not just NATA members — at PreventMisfueling.com.

The pilot training program is about seven minutes long, according to Mike France, NATA’s director of safety and training.

“To go through the line service track, it’s a little bit longer because the procedures are a little more in depth,” he said. “That’s about 15 minutes. None of the programs are longer than 17 minutes.”

In the first two months the program was online, more than 1,500 people completed it, according to France.

There are several different types of misfueling. The obvious one is getting the wrong grade of fuel — Jet A instead of 100LL. But there’s also getting the wrong amount of fuel and improper distribution, according to France.

“It’s anything that goes against the fuel order,” he said. “Obviously, all of those can be harmful.”

The most harmful is the delivery of the improper grade of fuel. “We’re talking about severe engine damage or an engine failure type of situation,” he said.

According to Ben Visser, General Aviation News’ fuels expert, there’s not much of a problem if 100LL is accidentally put into a jet engine.

“I would not expect much to happen because a jet engine is like a blow torch or furnace,” he said. “If you can pump it and it will burn, the engine is OK. There are some explosive issues with refueling and excessive use of a leaded fuel can cause burner deposit, but short term not much will happen.”

Adding Jet A to an engine that runs on 100LL is a whole other problem.

“Adding Jet A reduces the octane over one octane per percentage of contamination,” he said. “So if you put 25% Jet A in an 100LL engine, you would have an octane of about 70 to 75 octane. This would cause knocking on even an 80/87 engine and would definitely destroy a 100/130 engine.”

“The biggest problem here is that the engine will start on the uncontaminated fuel in the fuel line and carb,” he continued. “Now on takeoff, you burn through the good gas and get to the contaminated fuel during climb-out, which is the most vulnerable time. The engine will usually hammer for a few seconds and then, depending on the contamination level, either quit or destroy a piston or two. If you are lucky, you will burn the good fuel in the system on the taxiway and the engine will quit. But most of the time it happens in the air.”

What are the costs associated with misfueling? On the low side, it will be a borescope check and maybe an oil analysis if it knocks on taxi, Visser said.

“If there are any signs of heavy knock, which will look like some areas of the pistons have been sand blasted, then it will require a complete teardown or even an overhaul. In both of these cases, the fuel tanks and system will need to be drained and flushed. The third option would be a crash, which would be very, very expensive.”

Putting in the wrong amount of fuel can be just as dangerous from the perspective of weight and balance or maximum takeoff weight.

“In a lot of general aviation aircraft, if you’ve got a full load of passengers and baggage, you might not want a full load of fuel,” France said. “A top off in that situation could result in a potentially hazardous situation.”

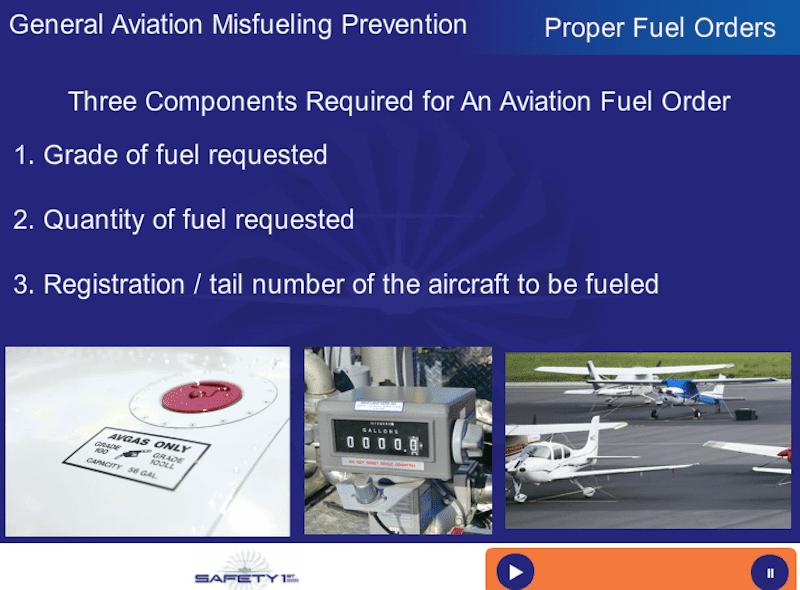

In most misfueling situations, miscommunication is the culprit. The training stresses that pilots should give FBO personnel three important pieces of information every time their plane is fueled: Fuel grade, amount of fuel, and tail number.

France recalls the days when he was a lineman at an FBO. “So many people would walk in and say, ‘hey can I get a top off on my Mooney?’ That is missing the key pieces of information, including the grade of fuel and the tail number. Make sure you have a clear line of communication on all three of those: Grade of fuel, quantity, and tail number.”

“Preventing misfueling is not a complex process,” he continued. “It’s something that you have to do over and over again, thousands and thousands of times. Just make sure you do it right each time.”

Complacency can be a problem, especially when the same FBO fuels your airplane every time. But don’t become a statistic, France warns.

That’s why NATA encourages FBO personnel to make it standard procedure to get the three key pieces of information for every fuel order, whether it’s the first time they’ve seen the plane or one that is based at the airport and is fueled regularly.

“It’s important for these procedures to become an ingrained part of the way you do something every single time so you don’t get complacent and begin to stray off the line of what is acceptable procedure,” he said.

But aren’t there safeguards in place?

Planes all should have placards on the wings with the acceptable grade of fuel. And filler ports are different for Jet A and 100LL — and it’s important for pilots to know what type of filler port their airplane has.

“Typically aircraft that are powered by avgas have the narrow filler port opening so that the larger Jet A nozzle can’t fit into that port,” France noted. “But a lot of older aircraft that require avgas still have the large opening and a jet nozzle can fit in there. If that’s my aircraft, I want be aware that I’m at a higher risk for misfueling because a Jet A oval spout will fit into my filler port.

“If I fly a Piper Meridian that takes Jet A, I need to understand that the Jet A large nozzle won’t fit into those outer tanks,” he continued. “They are going to have to use an adapter. I’m going to risk maybe something happening there.”

And realize too, that FBO personnel are dealing with different sized nozzles. In the Cessna 421 accident, the FBO employee told the NTSB that the nozzle on the Jet A fuel truck was small and round like the nozzle on the avgas truck.

According to the airport manager, the larger Jet A nozzle, which was J-shaped with an opening of 2-3/4 inches, had recently been switched to a smaller, round nozzle.

Switching to a smaller nozzle increased the chances that aircraft that need 100LL fuel could be misfueled with Jet A, NTSB officials said in the accident report.

How can pilots protect themselves and their aircraft? First, buy your fuel from a known FBO with a good reputation, according to GAN’s Visser.

“Second, if you have a Turbo 210, or any name with Turbo in it, get rid of the name so that fuel people are not confused,” he said.

Third, he advises you stay with your plane during refueling, especially at a “new to you” FBO.

“Take the time to be there when the aircraft gets refueled,” France agreed. “Say hello to the fueler. See the truck that is coming up. Ask questions if you need to.”

Not many pilots actually do this, according to Paul Deres, director of education for the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association Air Safety Institute, who helped develop content for the online program.

“Many years ago, I worked line service at a FBO down in North Carolina,” he recalled. “We’d fuel all the flight school airplanes, and of course, take care of all the airplanes coming in and out of the airport. I don’t recall ever having a pilot monitor the fueling operation. They go inside, use the restroom, get a snack, come out, and I was probably the same way through most of my GA flying. We assume, ‘Hey, this guy knows what he’s doing. I’m sure it’s the right kind of fuel.’”

A final check is to look at your receipt. It will say what kind of fuel was put into your plane. In the Cessna 421 accident, the receipt clearly said Jet A.

“Unfortunately, misfueling related accidents have occurred and people have died when it could have been prevented had the pilot looked at the receipt that said Jet A right on it instead of avgas, which is what he was expecting,” France said. “He didn’t read it. He folded it up and went on.”

Source: http://generalaviationnews.comNew training aims to prevent misfueling