Dispatch from KMHE, Mitchell, South Dakota: An airplane. High above me and slightly to the left. I nudge my 14-year-old son, Rio, with my elbow and point up through the canopy. His dark brown eyes, hawk-like when he’s flying, narrow as he studies the silhouette. “It’s white,” his voice crackles through my headset. “It’s not him.”

Rio, the ink on his student pilot ticket barely dry, is in command. He has us dead on course, and climbing slowly, which is the plan. We know there are good tailwinds aloft, starting at either 6,000 feet or 7,000 feet, depending on which forecast you believe, so the only question is: What’s the best way to get up there?

There are two choices: Climb sharply to get up there as quickly as possible, which sacrifices speed over the course; or climb more slowly and keep up a faster ground speed on our way to altitude.

As it’s a long race — the 400-mile AirVenture Cup Race — and as our climb performance ain’t so great, we decide the slow and steady climb is the bet most likely to pay off for us.

At the start of the race 15 minutes ago, Rio and I were the first to lift off. As soon as we heard our time “hack” on the radio, I banked sharply onto course, keeping low and building speed. I glanced over my shoulder out the large back windows of Race 53 and saw the second plane take off. My competitor, standing on his tail, climbing so steeply I wondered if he’d stall. Clearly, he’d chosen the other option.

Which one of us made the right call?

The AirVenture Cup ramp at Mitchell, S.D., was open to the public the day before the race, and is a popular attraction with the local community. Young Eagles flights where given, and race organizers suspect that the actual 2 millionth Young Eagle received his or her flight in one of the race planes the day before the race. (Photo by William E. Dubois)

I detect motion in my peripheral vision. Above, and to the right this time, a second plane slides past us. Our strategy is beginning to look like a losing bet. “Low wing,” says Rio, “it’s not him.”

I scan our panel. Oil temp and pressure good. Cylinder head temp normal. We’re full throttle, but our airspeed sucks. I’m not happy about that. Of course, we’re heavier than usual. We’re in a long race, so we’ve got more fuel than I usually race with, plus there’s two of us in the plane.

I usually race alone, as weight costs speed. But family is more important than winning, so I told Rio to choose one race to copilot this season, and this is the one he chose: The 19th running of the AirVenture Cup, the air race that kicks off the world’s premier aviation gathering at Oshkosh, Wisconsin.

The AirVenture Cup

The Cup isn’t a Sport Air Racing League event. In fact, the race is nearly twice as old as our league, but league members get season points for flying it.

Race 53 arriving at Mitchell, SD, the day before the AirVenture Cup. The plan had been to arrive a day earlier, but racing is full of uncertainties. Triple-digit temps across the Midwest, and a flat tire on the nose gear caused delays. Note the newest speed mod: Nose gear pants. (Photo by Lisa F. Bentson)

It’s a big race, with 71 planes turning out this year. You can read that number, but you can’t grasp just how many planes that really is until you’re actually standing in the middle of a ramp surrounded by 71 race planes. What’s that feel like?

Electrifying.

Planes as far as the eye can see. There’s no describing the feeling of being on a ramp with over 70 race planes. The excitement was electric. (Photo by William E. Dubois)

There were planes of every size and shape and size and color. High wings. Low wings. Canards. Trikes and tail wheels. Homebuilts and factory planes, it’s a living encyclopedia of aircraft.

The pilots are an international lineup. Some are famous — Reno racer John Parker is here with his Thunder Mustang Blue Thunder II, and Mike Patey is here with his souped-up turbine Lancair Turbulence — and others are just everyday people. This year’s race boasts 25 rookie racers flying the AirVenture Cup for the first time.

Linemen pull Race 53 to the refueling point shortly after landing at Mitchell, SD. In the cockpit co-pilot Rio A. F. Dubois (left) relaxes, while air racer William E. Dubois downs a much-needed cold water. After fueling, the linemen tied the plane down with a speed that would have made rodeo stars proud. (Photo by Lisa F. Bentson)

Of course, our competitors for the league season champ trophy, Team Ely are here, head-to-head against Race 170, a Cessna 170B, which won’t even be a contest.

We, on the other hand, are more closely matched in our heat.

A bad moment

“It’s not him,” Rio announces, as a third plane — red and white —passes overhead. A sinking feeling is setting in, being over-flown by so many other planes. But these planes don’t matter. Only one other plane matters.

I look directly above us, straight up through the four-inch gap between the two canopy halves we’ve cracked open for fresh air. High above in the dark blue sky is a silver plane. The unmistakable lines of a vintage Cessna. Steadily, methodically, it overtakes us. Passes us. Heads off to the east, leaving us behind.

I’d half expected this to happen, but I’m unprepared for the impact. My heart suddenly gets heavy. A pit forms in my stomach. A brief wave of nausea passes over me. We’ve just lost the race.

And maybe the season.

“It’s him,” I say.

Him

Him is Dane Pruitt, piloting Race 207, a sleek and lovingly restored Cessna 120 that was found in a chicken coop. Dane and I have exchanged emails a few times, but I’d met him for the first time less than 24 hours before. He’s tall and thin, and he was wearing a straw hat, blue overalls, and sandals. He made a beeline across the crowded tarmac of the Mitchell Municipal Airport and stuck his hand out in greeting.

In his casual Arkansas accent, he told me he was convinced he was slower than we were, but I knew better. I’d studied the cruise, climb, and maximum speeds of his craft, and I’d seen Race 207 in person 30 minutes prior. She’s polished, keeping her light and letting her cut through the air smoothly. She had wheel pants to reduce drag, and unlike most older planes, she didn’t have a drag-inducing venturi hanging into the slipstream to power gyros.

All in all, she looked like antique aerodynamic quick silver.

Still, I’d let myself believe that we could somehow beat her. All kinds of things can happen in air racing. I’d beat better planes before by being a better pilot.

Dane, however, is a heck of a good pilot. He’s been around planes since he was a tot. Later his brother, Jamon Pruitt, showed me a faded color snap shot of the two brothers as small children standing in front of their father’s airplane. I bet they were flying airplanes before they’d mastered tricycles.

Dane and Jamon Pruitt

Their father, Jimmy Pruitt, was on hand for the race, too, having arrived with Dane in the 120. He had planned to race with Dane, but in the end decided the 120 was too cramped, so he rode with his other son in Race 200, a speedy Meyers 200D.

Jimmy is… how should I say it … a bit… direct? In your face, others might say. His soul shines with a flint-like competitive spirit, and he made no bones about his desire for his son to beat me. The two boys seem a bit embarrassed by their father’s directness, but I loved the old coot right off the bat. As a father myself, I know how it is with fathers and sons, and our desire for our boys to win.

Second chance

The weather gods were up to their old tricks on race day, forcing the entire race fleet to put down at the penalty-free fuel stop at Owatonna Degner Regional in Minnesota, which normally would have been used by only a half a dozen of us with shorter-range planes. The small tarmac was so packed with planes that it resembled the deck of a battle-ready aircraft carrier.

Racers make their way to their planes at dawn. The skies above the flight line before the start of the AirVenture Cup race suggested fine weather, but farther up the course conditions were IFR, prompting both a delay in launch and a mid-race stop for all 71 race planes at Owatonna, Illinois. (Photo by William E. Dubois)

In bright sunlight, scores of pilots stared in disbelief at tablets and smart phones, which showed IFR weather stubbornly couching over our route ahead.

Air racing is a VFR sport. So we waited.

And waited…

And waited…

There was talk of canceling the second half of the race. There was talk of making it a two-part race.

We waited…

And waited…

Pizzas were brought in to feed the flight crews. There were too many of us for one pizza parlor, so we ate from boxes with the logos of Dominos, Godfathers, and Pizza Hut.

Everything was sunny and bright at Owatonna, Illinois, but IFR weather up the course forced the landing of all the race planes at what should have been a fuel stop only for the racers with the shortest range. (Photo by William E. Dubois)

In the late afternoon, in blustery winds, the weather cleared ahead and the race was on again. This time Rio and I were far down in the starting order. We stood by our plane watching the speed demons snarl and whine down the runway and off into the blue sky until the ramp marshal jogged up and spun his arm, lasso-like, above his head.

Start your engines.

We lined up two abreast on the runway, alternating our takeoffs left and right when the green starting flag was dropped. This time Dane Pruitt was ahead of me. Conditions had changed, but his battle plan had not. He lifted off and pointed his nose to the sky. I banked onto course over the cornfields and watched with great satisfaction as we easily slid under him and watched him drop behind until he became a speck and finally disappeared from sight.

It was delightful.

Our first defeat

The AirVenture Cup is no Sport Air Racing League race with its dizzying sharp turns and adrenaline-packed course. The Cup is more like a commute to a race than a race itself.

Winning is an exercise in exactitude: Staying on course, ferreting out favorable winds.

Dane Pruitt somewhere behind us, Rio and I focused on the boring, but critical, businesses of flying with airline accuracy and military precision.

A happy moment early in the flight: Rio A. F. Dubois (left) pilots Race 53 shortly after take off, while pilot-in-command William E. Dubois scans the panel. 14-year-old Rio was the youngest certificated student pilot in this year’s race, and one of the youngest in race history. (Photo by William E. Dubois)

But it was not our day to win. Dane caught up with us at the Wisconsin border. As we slid over the Mississippi River, he slid over the top of us, high above, and disappeared into the distant horizon. We knew we were beaten, but the day was so beautiful we hardly cared. Race 53 was making good headway, and the sky was clear and smooth, and we were together, enjoying each other’s company as we plied the skies.

The race officially ended with a low pass over the numbers at Taylor County airport in Medford, Wisconsin, with recovery of the planes at Wausau, 35 miles away.

Race 53 at AirVenture in Oshkosh, WI, with a familiar air traffic control tower in the background. For one week each year, this tower is the busiest in the world. (Photo by William E. Dubois)

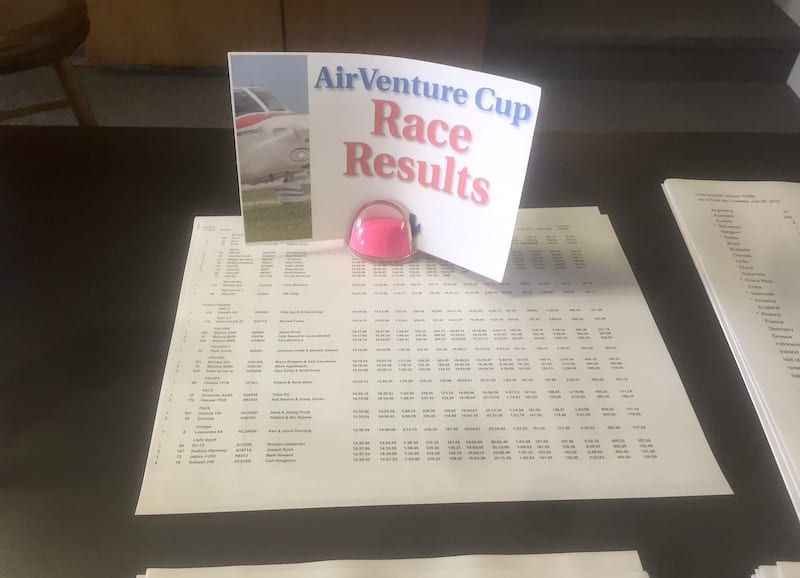

It wasn’t until the next night — at the awards ceremony at AirVenture — that we learned just how badly we’d been beaten. Our average time for the two-leg race was 118.92 miles per hour, the second-slowest of the fleet of race planes (a vintage Luscombe 8A coming in last at 111.32 mph).

Race 53 was front and center for the air shows at AirVenture this year, but did not participate in any. It was the first time either the pilot or co-pilot had flown into AirVenture. They read the NOTAM dozens of times, and report that the actual experience is not nearly as intimidating as it sounds. (Photo by Lisa F. Bentson)

And not only did we lose to Dane, we lost by a landslide. He clocked a speed of 131.14 mph, besting us by over 12 miles an hour, completing the course 18 minutes and 49 seconds faster than we did. We weren’t just beaten. We were slaughtered.

At the other end of the spectrum, Mike Patey set a new record for the Cup at 438.02 mph.

Due to the sheer size of the race this year, the awards were held the next day in the Forums and the grounds of AirVenture. First, second, and third place trophies were given out in all classes. Nope, the AirVenture Cup does not give out a cup. (Photo by William E. Dubois)

As Rio and I went up to accept our second-place trophy, I was trying to make sense of our speed. Granted, it was our best race speed of the season, but unlike the roughly circular SARL races, the AirVenture Cup is a one-way cross-country race, this year with a tailwind. Most of the way I was seeing ground speeds much higher that that.

Now and forever an air racer, 14-year-old Rio A. F. Dubois displays the 2nd Place Fac 6 Class trophy he and his father won in the 19th Annual AirVenture Cup. (Photo by William E. Dubois)

Still, my heart filled with pride for Rio’s hard work, and up on the stage, as race co-chair Joe Coraggio started to hand me the trophy, I signaled him to hand it to Rio. This was his race, and even though we didn’t win first place, we were the winners in my book.

In racing we might be in second place, but in family bonds, like the Pruitts, we couldn’t be beat.

Fathers and sons

At the after party, at Wendt’s on the Lake, I sought out Dane to congratulate him on a race well flown. He was modest and polite, and we traded stories of what we saw and what we where thinking at various points on the course.

Father Pruitt was there, too, bursting with pride in his son’s victory. I told him his son was the first to beat us. He rested a hand on my shoulder and told me, “Everyone has to lose sooner or later, and sometimes it’s better to lose.”

“We both know that’s not true,” I replied, “but your son flew smart and well, and kicked my ass fair and square.”

His eyes sparkled with pride. I don’t like losing, but it was almost worth it to make the old man so happy.

Almost.

The celebration following Race 53’s finish in the AirVenture Cup—or so it seemed like to the Race 53 team, who found a solid mass of humanity packed around the vintage race plane right before the Wednesday Night Air Show. One benefit of a late arrival was a parking place at the very end of the Race Corral, near the taxiway, affording a magnificent view of the night’s fireworks, seen here both above, and reflected off of, the wing of Race 53. (Photo by William E. Dubois)

Jamon also took first place in the race among three Meyers 200s, with a speed of 221.78 mph. It was a good night for the Pruitt boys. Both generations.

But it was a good night for the Dubois boys, too. Rio, early in his pilot career, had flown his first air race. He was the youngest student pilot in this year’s race, and one of the youngest in race history. And in the tradition of air racing, once you’ve flown your first race, you will always be an air racer.

Just like Jimmy Pruitt, I couldn’t be prouder of my son.

My son, the air racer.

My League Points: 820. I’m now a full 50 points behind Team Ely’s 870 points. They widened their lead by beating the one other plane in their heat and picking up 110 points. I, having lost my heat to the only other plane flying in my class, get only 80 points for coming in second place. With only seven races remaining in the season, it seems doubtful that I can catch up to the Elys, much less pull ahead. But the one thing you can count on in air racing, is that you can’t count on anything.

My League Points: 820. I’m now a full 50 points behind Team Ely’s 870 points. They widened their lead by beating the one other plane in their heat and picking up 110 points. I, having lost my heat to the only other plane flying in my class, get only 80 points for coming in second place. With only seven races remaining in the season, it seems doubtful that I can catch up to the Elys, much less pull ahead. But the one thing you can count on in air racing, is that you can’t count on anything.

My League Standing: I’m now tied for second place overall, neck and neck with Jeff Barnes of 411, who flies in the Experimental Category. The Elys continue to hold the top of the leaderboard, but stayed for neither the awards nor the party. I don’t think they are having as much fun defending their title as I am trying to steal it.

Source: http://generalaviationnews.comAir Racing from the Cockpit: Family Jewels