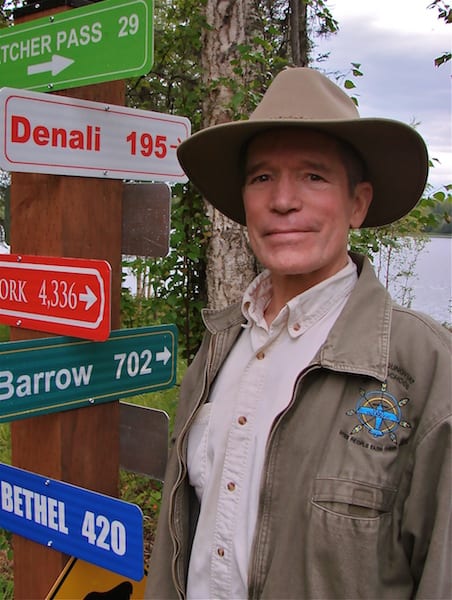

By MIKE LUCAS

As I removed my shirt and sat up on the examination table, my Aviation Medical Examiner (AME) asked me: “Have you seen a doctor lately?”

The question was curious to me. I have been visiting an AME physician every year since 1985. That question was, it seemed, a trick question, I was sitting in a doctor’s office. After my examination, I received my second class medical certificate that day.

The interesting point about this exchange with my AME that August is that 10 months later, the next June, I was on an operating table, scheduled for a quadruple bypass surgery.

It was impossible: I was active. I stood 5 foot, 9 inches, weighing 172 pounds. Cholesterol was low. I am the type of person that takes the stairs instead of an elevator. I never failed an aviation medical exam, or even came close to failing.

It was impossible: I was active. I stood 5 foot, 9 inches, weighing 172 pounds. Cholesterol was low. I am the type of person that takes the stairs instead of an elevator. I never failed an aviation medical exam, or even came close to failing.

In aviation, however, we have seen the impossible happen many times.

I’m a pilot, I need my “medical” to fly. As a human being, you need your health too.

Most pilots stay healthy to keep their medical status, thinking that an FAA medical is insurance against dying from some horrible malady far into the future.

Many pilots are afraid of health care, and find out what is needed to make things go smoothly at a medical exam and leave it at that, thinking they are saved for another year or two.

I know that after 30 years of flying, dozens of certificates and a hundred checkrides, your flying privileges can stop immediately when a letter arrives in your mailbox from the FAA requesting that you send your medical certificate to their office immediately.

When a pilot visits an AME, he is not really in attendance with a doctor in the traditional sense. The task of an AME is to ensure that the applicant meets the standards set by the FAA. The AME is less a doctor and more a representative of the federal government.

She is not there to take care of your health, or for preventative medicine — she is there to make sure you are fit to fly.

Photo courtesy FreeImages.com/Kurhan

The federal government, as represented by the FAA, does not care about your health. The FAA is only concerned that you do not drop dead while flying, kill yourself, someone else, or damage property. The exam is not directed at preventative medicine or general health, only issues that impact aviation safety. The AME is asking the question: Does this person’s body function well enough to fly?

Staying healthy enough to keep your medical certificate is a short-sighted strategy. There are several other areas that aviation medicine does not address.

Perhaps you are at your favorite AME, between flights, in a hurry. Does the examiner check for swollen glands or an enlarged thyroid? How about your skin for a possible cancer? At age 50, AMEs don’t screen for colon cancer, and it is the opinion of one AME that a blood pressure of 155/95 is good enough for flying in America, but not good enough for general health.

Some AMEs feel that if you don’t use it for flying, then why check it? There goes the prostate exam. The urine sample may not catch diabetes, and in 30 minutes, can an AME screen for psychological issues, substance abuse and chemical abuse?

An accurate medical exam depends on honesty, basing its integrity on the applicant’s truthful disclosure of their aero-medical condition on the MedXPress application.

An ideal aviation medical exam, if the applicant is healthy, should be nearly as complicated as pre-flighting a fixed gear Cessna. After all, there are some similarities: Checking pressures, the use of a dipstick, determining the colors and qualities of fluids, measuring the weight, and listening closely, to name a few.

An ideal aviation medical exam, if the applicant is healthy, should be nearly as complicated as pre-flighting a fixed gear Cessna. After all, there are some similarities: Checking pressures, the use of a dipstick, determining the colors and qualities of fluids, measuring the weight, and listening closely, to name a few.

The danger sign for me was when I was on a brisk walk back to the airport parking lot. I had a deep dull pain in the top of my chest, at the base of my throat. It was like an “ice cream headache” in my chest. I know these are not medically accurate terms, but that is what it felt like. Every time I took a short walk up a hill or even a flight of stairs, the pain at the top of my chest returned.

A week after my first painful treks, I was at the doctor’s office. An EKG at rest was non-conclusive, and I was scheduled for a stress test the following day, a Friday. I flunked the stress test. I was scheduled for a heart scan the following Monday.

I didn’t make it to Monday. Instead, I ended up at the emergency room the next day on the advice of a physician friend. Sunday was my scan, which showed 85% blockage, and Monday was a big time operation.

An important point in this dialogue is that you may have no known symptoms of coronary artery disease, cancer, or diabetes. Just because you have no known symptoms doesn’t mean the conditions are not detectable. You haven’t looked hard enough.

As a pilot, you must be your own director of maintenance. If you own an airplane, you probably take better care of your prized Taylorcraft than you do of yourself. You must search the Advisory Directives, Service Difficulties and Accident Reports on your own body or you will be grounded.

An FAA exam is not designed to maximize your lifespan. You may think you are living in the green arc, but you may be cruising in the yellow caution range. The FAA is only concerned if you are close to the red line.

You are only supposed to fly in the yellow arc in the rare instance of smooth air, not all the time, if it gets bumpy, slow down.

I am not a doctor, I am writing from experience, a few interviews and some limited research. If you have pain, go to a doctor. It’s better to live out your life as a writer, than to die sooner as a flyer.

Source: http://generalaviationnews.comHave you seen a doctor lately?