Imagine the plight of the first ancient mariner to point toward the horizon and say, “No more hugging the coastline for me, I’m going direct.” I think his name was Harpolos. For the purposes of this column, let’s say it was.

The townsfolk must have thought Harpolos was mad. Crazy as a loon. The rational man, the reasonable man, would think to himself, “What possible good can come from tempting fate? We hug the coastline because there are no monsters there. We know this to be true. No one but a lunatic would venture into the deepest waters to disappear over the horizon, very possibly to never return.”

And so it goes with discovery. There is always someone willing to give it a try, and there are always legions of nay-sayers who believe to their socks (or sandals) that the boldest among us are just plain nuts.

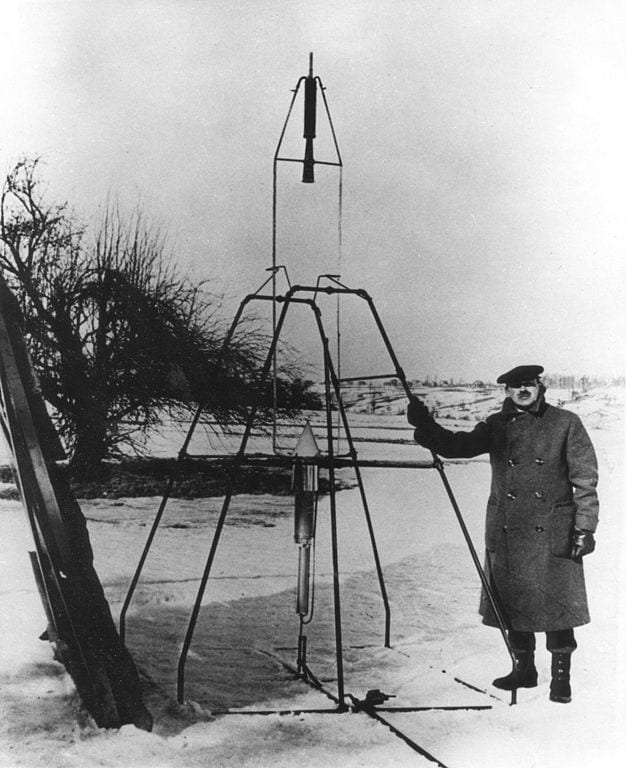

Robert Goddard may be the father of modern rocketry, but that didn’t stop the dunderheads at the New York Times from publicly mocking him in 1920. They apparently believed very strongly in the superiority of their understanding of rocketry, based no doubt on the extensive thought experiments they’d done in their heads. Goddard’s actual experiments and experience be damned. We’re the New York Times, we know what we’re talking about.

Robert Goddard, bundled against the cold weather of March 16, 1926, holds the launching frame of his most notable invention — the first liquid-fueled rocket. (NASA Photo)

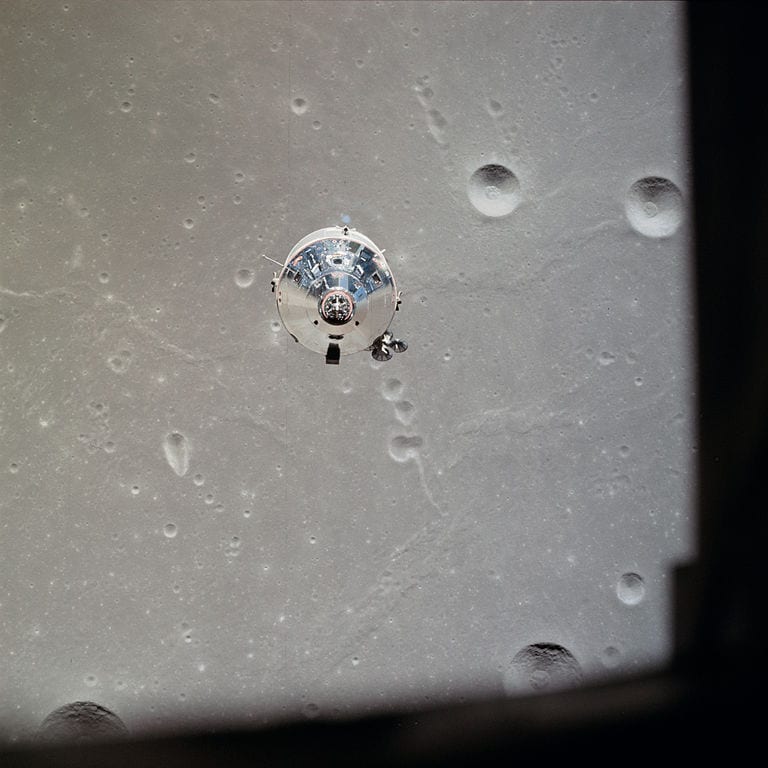

Or maybe not. The paper did issue a retraction of sorts 49 years later, the day after Apollo 11 launched on humankind’s third manned mission to the moon. Not the first mission. Not the second. The third.

Oops. Wrong again. How embarrassing.

Apollo 11 Command/Service Module Columbia in lunar orbit, photographed from the Lunar Module Eagle. (NASA photo)

Human nature being what it is, there seems to be nothing more daunting than fear of the unknown and embarrassment. Combine the two and you’ve got the fear of embarrassment. Now that’s powerful stuff.

Perhaps that’s why public speaking is such a bugaboo issue with so many people. It wraps the two things we are most leery of into a single kryptonite-like package that weakens the knees, unsettles the stomach, and brings on a humiliating episode of flop sweat.

We fear what we don’t understand. And there’s a lot we don’t understand.

My friend Greg wrote me this morning to ask how it was he saw an airplane flying into LAX the other day that appeared to be standing still. He was perplexed.

Greg has seen things. He’s a U.S. Marine. A very colorful and proud Marine, too. So much so that he wrote a book about his experience as a jarhead. It’s called “The Pink Marine.” Read it. You’ll be thoroughly entertained. I was.

In any case, Greg is no fool. He knows that airplanes can’t stand still in the air. Not unless they’re Harriers or Ospreys. And a Marine Sergeant would be able to tell the difference between a military fighting aircraft and a commercial carrier.

In this case, the airplane said “Emirates” on the side, which suggests he was looking at a Boeing 777 or something from the Airbus family of transport category aircraft.

My buddy Greg was more than likely experiencing an optical illusion. One that’s common enough that YouTube carries a number of videos posted by incredulous people who can’t for the life of them figure out how that big ol’ airplane is just standing still in space.

Check it out, you’ll see. This is a very common optical illusion that has led to a real sense among certain members of the public that aviation is just…“It’s beyond understanding, I tell ya.”

A PROBLEM

Our industry has a problem. The average man or woman on the street doesn’t understand how we work, or why general aviation is important to their way of life. That’s not ideal for us.

Worse, our general aviation airports are in many cases owned by municipalities that have no idea what benefits an airport can bring to their little burg, and too often they are operated by municipal employees who have no real understanding of how to market their facilities and services.

Imagine that ancient city with the bold sailor planning to head into the briny deep. What if the city elders decided that it’s the better part of valor to close the port rather than risk those damn sea monsters wading ashore one night to loot the town and kill everyone in their sleep. That could happen, right? Especially if that nutcase, Harpolos launches off and sails right over their head’s. Of course the sea creatures will attack us. That’s a no-brainer.

Closing the port couldn’t have an adverse effect on the economy of Crete, could it?

Or what if somebody at the National Committee for Aeronautics (NACA was the predecessor to NASA) read that New York Times piece about Robert Goddard and decided to shut down the research program entirely.

After all, rockets can’t fly in space. There’s nothing for them to push against in a vacuum. Everybody knows that. We’re just wasting money and risking lives. Shut it down, close the doors, and send everyone home. The space program is nothing but a pipe dream. The New York Times said so, for goodness sake.

You didn’t want to watch HBO, make a long distance phone call, or use your GPS, did you?

Since most of the people we encounter during the day have no real understanding of general aviation, perhaps the answer to this foolishness can be found by talking to our stakeholders in terms they understand a bit better.

Let’s consider money as a primary motivator.

In 2013 the total contribution of general aviation to the U.S. economy was in excess of $109 billion. I can’t think of too many towns or cities that wouldn’t like to find a way to get cut in for a slice of that pie.

Of course the best way to make that happen is to become overtly general aviation friendly. And that starts with a well managed, customer-service oriented, all inclusive local airport that welcomes input from the industry it purports to serve.

Or we could just continue to be afraid of the sea monsters.

Source: http://generalaviationnews.comIt’s beyond understanding, I tell ya