Are U.S. sales or registrations of Light-Sport Aircraft near where they were expected to be by now? The short answer is, no, but more finesse is needed to obtain a complete answer.

While the numbers entering the U.S. fleet are well below forecasts from 2004, a couple obvious reasons help explain the shortfall.

The Sport Pilot/Light-Sport Aircraft (SP/LSA) regulation became effective in fall of 2004. A mere three years later — following a vigorous period of filling long-pent-up demand — the bottom fell out of the market, not just for aviation but for whole economies, globally.

Three more years later, in the fall of 2011, the Experimental Aircraft Association (EAA) and the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association (AOPA) teamed up to attempt eradication of the third-class medical.

While LSA producers have largely moved on, many orders were immediately put on hold because of this announcement.

For perspective, it’s worth noting that for years LSA registrations have closely mirrored Type Certified single engine piston sales. LSA are steady at roughly 25% of TC deliveries in the USA.

Can the airframe producer community lift itself?

Recently a colleague and I visited FAA headquarters in Washington, D.C. We had arranged a meeting with several top agency executives to talk about how the now-12-year-old Sport Pilot/Light-Sport Aircraft regulation might be improved based on the experience gathered.

With Sport Pilot (the new certificate) and LSA (the most affordable of newly manufactured airplanes), aviation has its best entry point for new pilots in decades. FAA officials agree with industry leaders that improving the breed is good for the users and good for the future growth and development of aviation.

Global Perspective

American pilots have it great in many ways. We can fly for hour upon hour in uncontrolled airspace. You don’t need permission for each flight. Airports and services are widely available across this large nation.

Yankee pilots can choose from a dizzying array of new aircraft and can browse large fleets of good, used airplanes to fit most budgets.

While the FARs make for some very thick books of dense reading, most recreational pilots can fly largely as they want without much interference.

Perhaps because of that abundance, we sometimes lose perspective on what happens around the world. No wonder. As the world aviation leader since Orville and Wilbur Wright, and certainly when viewing “traditional” general aviation, America is so far ahead that second place is hard to see.

However, overseas, interest in flying is strong. The main difference is foreign pilots primarily use other types of aircraft to satisfy their airborne yearnings.

Various factors are at work, but the price of aircraft in other countries is part of the explanation.

Fuel is another. With avgas running more than $10 a gallon, aircraft that burn 12 gallons an hour become viciously expensive to operate. This fact alone illustrates why Rotax is the most popular engine brand outside the U.S., given fuel burn rates between 3-5 gph, depending on how you operate.

Rotax can use — even prefers, running cleaner on — automobile gas, which further lowers the hourly operating expense.

Other reasons to choose LSA-like aircraft come from sophisticated avionics — nearly all LSA use digital instrumentation or “glass” — wide use of safety features like airframe parachutes, spacious cabins of modern design, and features like folding wings to make aircraft trailerable or more efficient when storing in hangars.

The 80/20 Rule

Everybody knows the 80/20 rule, where 80% of the sales are made by 20% of the producers. Here’s another variation on that rule.

In the world of Type Certified light aircraft, such as those from Cessna, Piper, Cirrus, Diamond and others, about 80% of the global fleet operates in the USA, while the rest of the world has about 20%.

Most TC aircraft builders are based in the USA, fuel is dramatically cheaper in America, and the large pilot population has vast expanses of mostly uncongested airspace in which to pursue aviation.

However, the aviation landscape changes when you examine it globally.

Look at certified aircraft in America. From its peak in 1978, U.S.-manufactured GA deliveries or new aircraft have fallen dramatically, by 93%, from 14,398 single engine piston aircraft built in 1978 to 986 in 2014.

Since 2000 the continuing drop is less severe. In 2006, manufacturers delivered 2,513 aircraft, so the decline to 986 in 2014 represents a drop of 61%.

Airplanes built during GA’s golden era in the 1960s and 1970s are mostly still operating. Presently, the average age of a four seater is 38.2 years.

As manufactured aircraft became increasingly expensive, experimental aircraft helped constrain costs since the 1980s. In the last two decades this sector has grown past 25,000 aircraft.

In the last decade, LSA have begun to add a different kind of new aircraft.

Thanks to long-lasting aircraft, the overall GA fleet has held reasonably steady despite the reduction in new aircraft manufacturing. The FAA’s registration database shows the certified fleet declined from a peak of piston-powered airplanes of 197,442 in 1984 to 137,655 in 2013, a drop of about 30%.

When you add experimental aircraft and LSA, total fleet numbers look relatively stable.

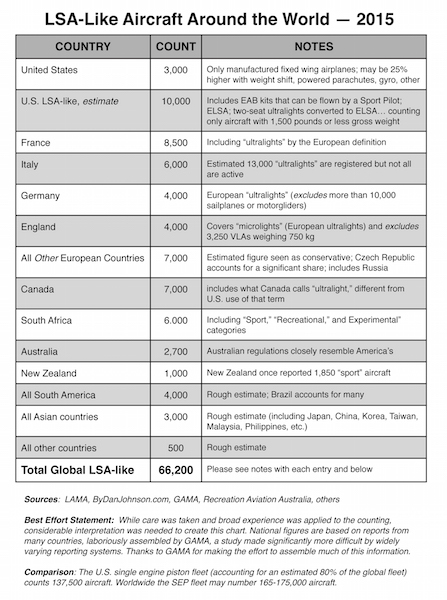

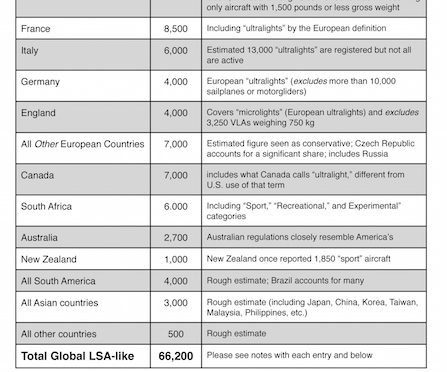

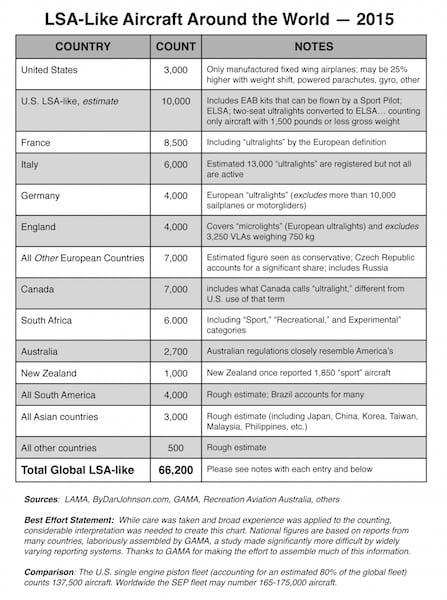

As we examine the entire globe, aviation sectors reverse. In the sphere of more affordable sport or recreational aircraft — what I’m calling “LSA-like” aircraft — only about 20% operate in the USA, while 80% fly above other countries. The chart shows the estimate for various countries.

One way we know this is by querying engine manufacturers. The largest of these, Rotax, reported that it has passed 50,000 deliveries of its four cylinder 80-100 horsepower 9-series engines.

One way we know this is by querying engine manufacturers. The largest of these, Rotax, reported that it has passed 50,000 deliveries of its four cylinder 80-100 horsepower 9-series engines.

This happened in the last 25 years, a period that mirrors the explosion of sport and recreational aircraft around the world even while the type certified world has contracted. The engine company conservatively powers about 75% of the international market.

Some Great (if Counterintuitive) News

Who is flying all those sport and recreational aircraft? From numerous conversations it appears most countries have situations similar to the U.S., but we have reliable data for the U.S., where half the world’s 1 million pilots reside.

Almost everybody in aviation worldwide frets over the declining pilot population. Who’s going to fly airliners in the future? Who is going to buy aircraft?

I unearthed a spark of light in the numbers.

From a peak of 827,071 licensed U.S. pilots in 1980 to the 2014 number of 593,499, we identify a drop of 28% over 34 years. Private pilot certificate holders fell by 51%, though many upgraded to higher certificates.

As pilots added skills, CFIs grew by 67% to become 17% of all certificate holders in the U.S. Pilots with instrument ratings increased by 18%.

Sport Pilot certificate holders now number 5,157, however, this amounts to less than 1% of all U.S. certificates. Nonetheless, with cost at one half to one third what it takes to earn a private pilot certificate, Sport Pilot seems sure to grow as new aviators take up flying.

Do you believe we’re all getting older and grayer? Many pilots think so, but the facts say otherwise. Here’s what I consider some very good news.

The biggest single category may be what you expect with those aged 50-64 numbering 179,277 pilots. Yet the surprising second largest segment is close behind.

Aviators aged 20-35 years old number 173,396 pilots. Clearly, younger Americans have a genuine interest in pursuing flight. As a near-term pilot shortage arrives, an aviation career starts to look better.

How We Counted

The information presented here relies partly on a solid effort by the General Aviation Manufacturers Association (GAMA). GAMA’s information is combined with regular reporting done on my website ByDanJohnson.com, in collaboration with my Light Aircraft Manufacturers Association counterpart, Jan Fridrich of LAMA Europe.

GAMA is focused on certified and business aircraft, but attempted to include all levels of aircraft in its country-by-country review.

To gather the numbers of recreational aircraft around the world I drew on GAMA’s data, along with reports assembled by Jan Fridrich, plus others.

Fridrich’s U.S. data comes from an examination of the FAA’s registration database.

For its information, GAMA was wholly dependent on reports it received from various civil aviation authorities in each country and the methods of reporting were far from consistent. By example, some countries listed as their smallest aircraft those weighing up to 5,700 kilograms (12,540 pounds).

We did additional research to distill only light aircraft generally under 750 kilograms or 1,650 pounds. Despite efforts to provide accurate information as represented in the nearby table, you should regard this analysis with some caution.

In Conclusion

Affordable aviation featuring the sector labeled LSA-like is active and flourishing when you assess the global impact of these flying machines. They account for about one-third of the world’s combined fleet of type certified aircraft and LSA-like aircraft.

Despite economic crises, wars, terrorism, and troubled areas of the planet, light aviation continues to grow and more nations are engaging. This shows the value of maintaining a worldwide perspective.

Source: http://generalaviationnews.comThe value of maintaining a worldwide perspective